Not All Barns Are Created Equal

One of the questions I am asked most frequently is: “How can you tell a good barn from a bad barn?” My answer to this question is that you must look at each barn carefully with an eye to a combination of history, craftsmanship and plain ole wear-and-tear, and you must have a trained eye to do it.

In our work we have looked at hundreds of barns over the years and have found that there are good barns and there are bad barns. There are barns surviving today from the age of hand-craftsmanship and there are barns that are products of the Industrial Revolution, during which time the methods of building barns shifted from quality hand-craftsmanship, meant to last centuries, to what we have come to identify as the planned obsolescence of the industrial era of the last two hundred years or so.

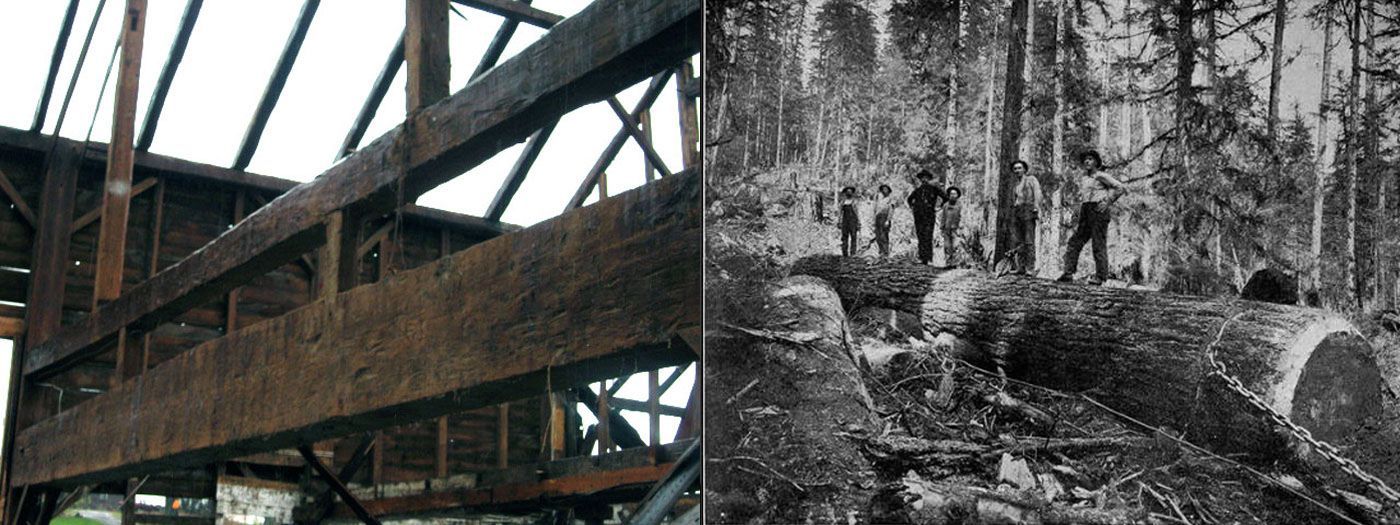

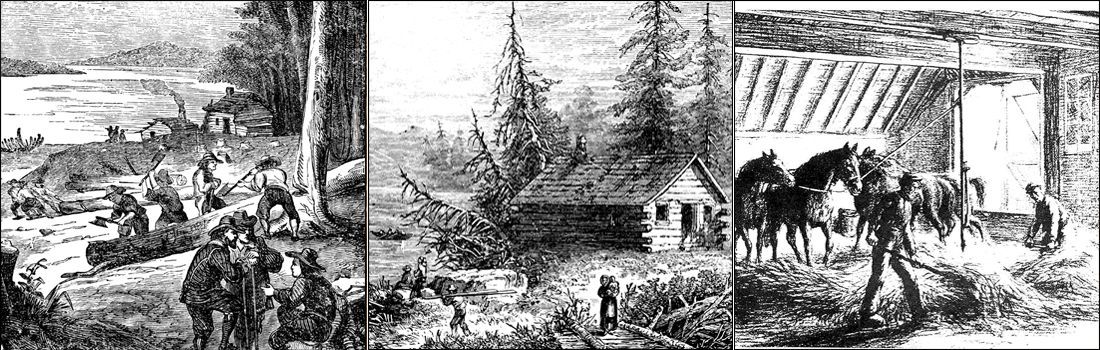

When barns were timber-framed in America during the 1600s and 1700s, they were intended to last for centuries. This means that the owners wanted a heavy timber frame protected from the elements by the roof and siding. Even though they knew the roof and siding would wear out and be replaced many times, and even the flooring would be pulled up and replaced, the core timber frame would remain.

So there are features to look for when buying a barn to be converted into a home. Here are some important ones:

Age: Generally speaking, the older a barn, the better it was crafted and the larger the timbers. This also means that the parts of the country on the East Coast that were settled earliest tend to have the oldest and nicest barns. But this also means that the older a barn is, the more it has been subjected to wear and tear, which brings up the subject of condition.

Condition: Even a well-crafted barn can have been neglected to the point of no return at which time it is not worth salvaging. The most important feature determining the condition of a barn is the roof. If the roof is intact and does not leak, it is likely that the barn under it is in good condition. On rare occasions, barns were neglected in the distant past and then given a new roof that then hides old rot. An experienced eye can determine this with some probing.

Joinery: A joiner is the person who cuts the end joints of beams into tenons and carves out the mortises, or squared holes, for these tenons to fit into. This is known as mortise and tenon joinery. (The fact that the spell check on my computer does not recognize “tenon” as a word, is proof of how the ancient process of hand joinery has been lost.) The quality of tenons, how tight they fit and how squarely and carefully they were shaped, is a direct reflection of the quality of a barn since it was a skill that could only be acquired with practice and a good teacher. As time passed into the later 1800s, the ancient art of mortise and tenon joinery was replaced with mechanical fasteners, spikes, bolts and plates. Finally, the heavy timbers themselves were replaced with smaller “dimensional lumber” like 2×4’s that were nailed together. So, with the passing away of hand-joinery went the ancient craft of timber framing.

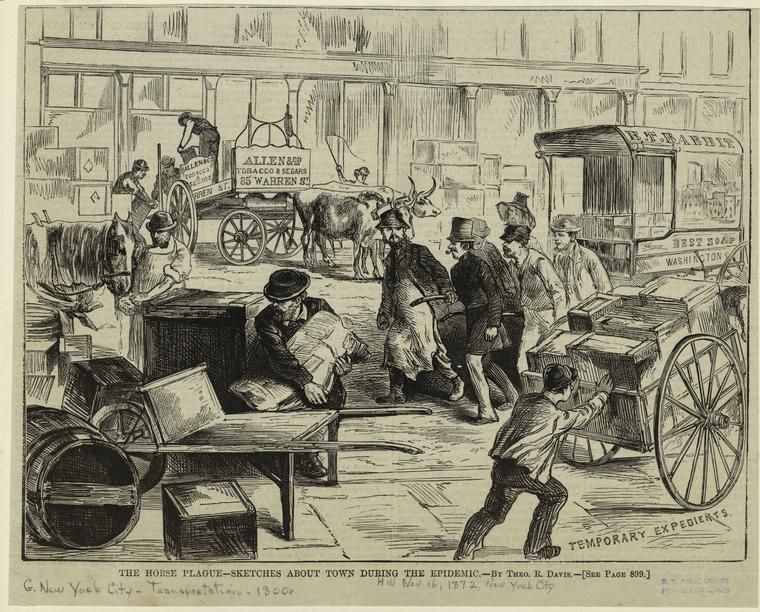

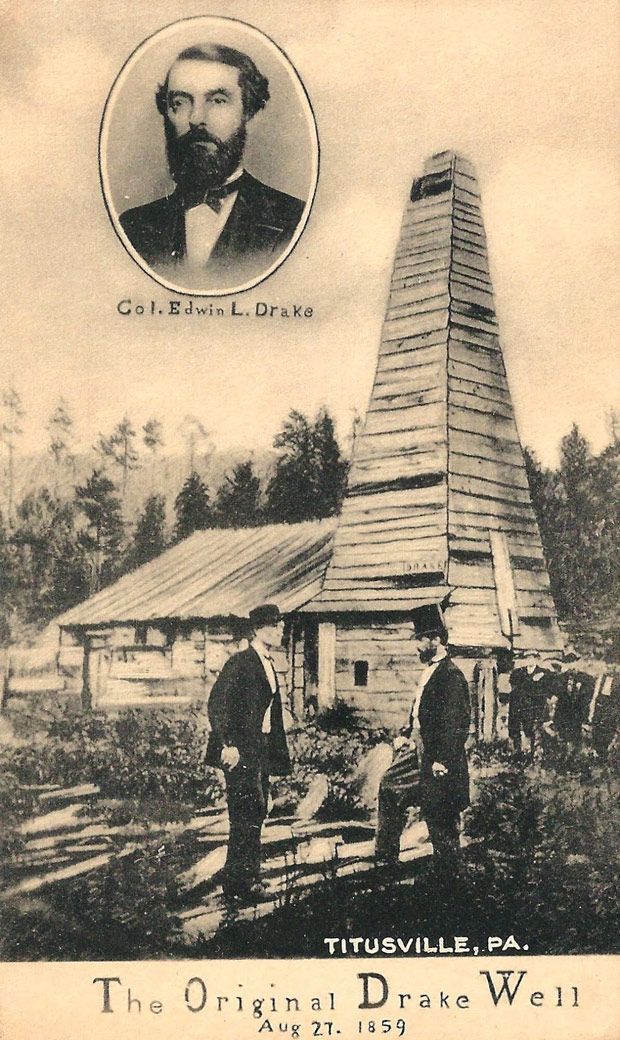

Wood species: Barns were invariably built with the woods from trees that were closest at hand. Generally, there are soft woods (hemlock and pine) and hardwoods (oak, chestnut, beech, poplar, maple). All of these woods make good timber frames. The hardwoods generally were made into lighter framed barns (timber dimension-wise) and the soft woods were more massively framed. Hand-hewn or sawn: The great labor in building a barn was in turning living trees into stable, square building timbers. This task could be accomplished mainly in two ways or in a combination of both. 1) The ancient process of felling a tree with an axe, and then using the axe to chop away the tree into the shape of a square beam was very labor intensive. This process is known as “hand-hewing” and was one of the first tasks that the industrial age tried to eliminate with a machine. And 2) the machine they invented was the saw mill. First the straight-cutting, vertical saw and later, about 1835, the circular saw. Prior to saw mills, there were hand-saws, but their use was limited to cutting tenons, cutting beams to length and in the case of a pit saw, sawing logs into boards.

As time progressed and sawmilling began to overtake and replace hand-hewing during the 1800’s, more and more barn timbers were sawn on mills, beginning with the smaller lengths like the knee braces, since they were most easily gotten to a saw mill. The longer lengths, like the huge top plates, were the last to be sawn on mills since they were simply of unmanageable length and difficult to transport to a sawmill.

One piece plates: the longest parts of a barn frame are the plates. There are two kinds of plates in a barn: top (resting on top of the side walls) and purlin, (supporting the rafters from underneath about in the middle of their length.) The plates run the length of a barn, and in earlier barns they were often one-piece, hewn from single trees. And these could be as long as sixty or even seventy feet!

As trees of such quality and length became rarer and sawmills preferred to cut shorter timbers, plates were sliced with joints called scarf joints. And as quality declined into the late 1800’s, mere “lap joints” joined plates end to end to make up the length of a barn.

Critters: it has been our experience that all barn frames have some current degree of bug infestation. The most pernicious of these critters is the powder post beetle, which defy all but the most complete treatments. To deny their presence is wishful thinking. To buy a barn that has not been fumigated properly is looking for trouble. Once built into a house, these pests have a way of making their presence known and are very expensive to get to move out. Don’t make the mistake of buying an untreated barn frame.

So, there you have a brief primer on what features to look for when barn shopping.